Illustrations by Naï Zakharia

East to Eden

by Roger Deakin, with Robert Macfarlane

Roger Deakin was a nature writer, broadcaster, and filmmaker who spent most of his life in Suffolk, in a ruined farmhouse that he restored. He is the author of Waterlog: A Swimmer’s Journey Through Britain, Wildwood: A Journey Through Trees, and Notes from Walnut Tree Farm, compiled posthumously from his diaries. He died in August 2006.

Robert Macfarlane is the author of books on nature, place, and people, including Underland: A Deep Time Journey, The Lost Words (with Jackie Morris), The Old Ways, The Wild Places, Mountains of the Mind, and Landmarks. His work has been widely adapted for film, television, music, dance, and stage, and translated into many languages. His writing has appeared in The New Yorker, Granta, and The Guardian. He won the 2017 E.M. Forster Award for Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He lives in Cambridge, England, where he is a Fellow of the University of Cambridge.

Naï Zakharia is an Illustrator living and working in Beirut, Lebanon. She obtained her BFA at the School of Visual Arts in New York City and works in the mediums of pen and ink, and watercolor.

Introduction

by Robert Macfarlane

In the summer of 2006, my friend the writer, forester, and naturalist Roger Deakin died of cancer, too fast and too young. A woodsman to the last, his pine coffin was decorated with a wreath of oak leaves, and his ashes were given to the earth in view of mature stands of cherry, oak, and silver birch. I was new to death then, but even had I not been, the loss of Roger would still have struck hard to my heart. “I want my friends to come up unstoppably, like weeds,” Roger wrote once in a journal entry, and our friendship, though only a handful of years old, was a weedy one, flourishing out of all proportion to its calendar.

Roger’s abrupt death felt most cruel to me in its lopping of future growth. We had made such plans! To stake out the badger setts in a wood near Roger’s Suffolk home at Walnut Tree Farm, with some infra-red goggles that Roger was confident he could source. To construct a coracle (birchwood frame, cowhide hull), and then paddle it across a meaningful stretch of ocean—or, failing that, across a good-sized pond. There were books to write together, conservation battles to fight, television programmes to make, jokes to tell, and all those unfinished—no, unstarted—conversations that, in the manner of conversations with Roger, would rapidly branch outwards, ending very far from where they had first taken root.

Roger was many things—a filmmaker, environmentalist, campaigner, poet, teacher—but he became best known for his trilogy of extraordinary non-fiction books about nature, people, and place: Waterlog (1999), his classic account of swimming through Britain’s rivers, lakes, estuaries, and lochs; Wildwood: A Journey Through Trees (2007), which describes his years spent travelling through forests and woodland cultures in Britain, Australia, Europe, and Central Asia, as well as chronicling his long family history of radical and community involvement with trees and forestry (“I am a woodlander,” he wrote in the opening pages of that book, “I have sap in my veins”); and Notes from Walnut Tree Farm (2008), which gathers decades of his writing about his home landscape in Suffolk. Roger travelled widely but always returned to that timber-framed farmhouse and the twelve acres of meadow, hedgerow, and copse that surrounded it. This was his fixed point, where one foot of his compass was planted, while the other roved and circled.

What follows here is a chapter from Roger’s Wildwood, to which I have written a short postscript essay that tells—by means of the story of a seed and a tree—how Roger continues to root and branch through my life and the lives of many others, long after his death.1

East to Eden

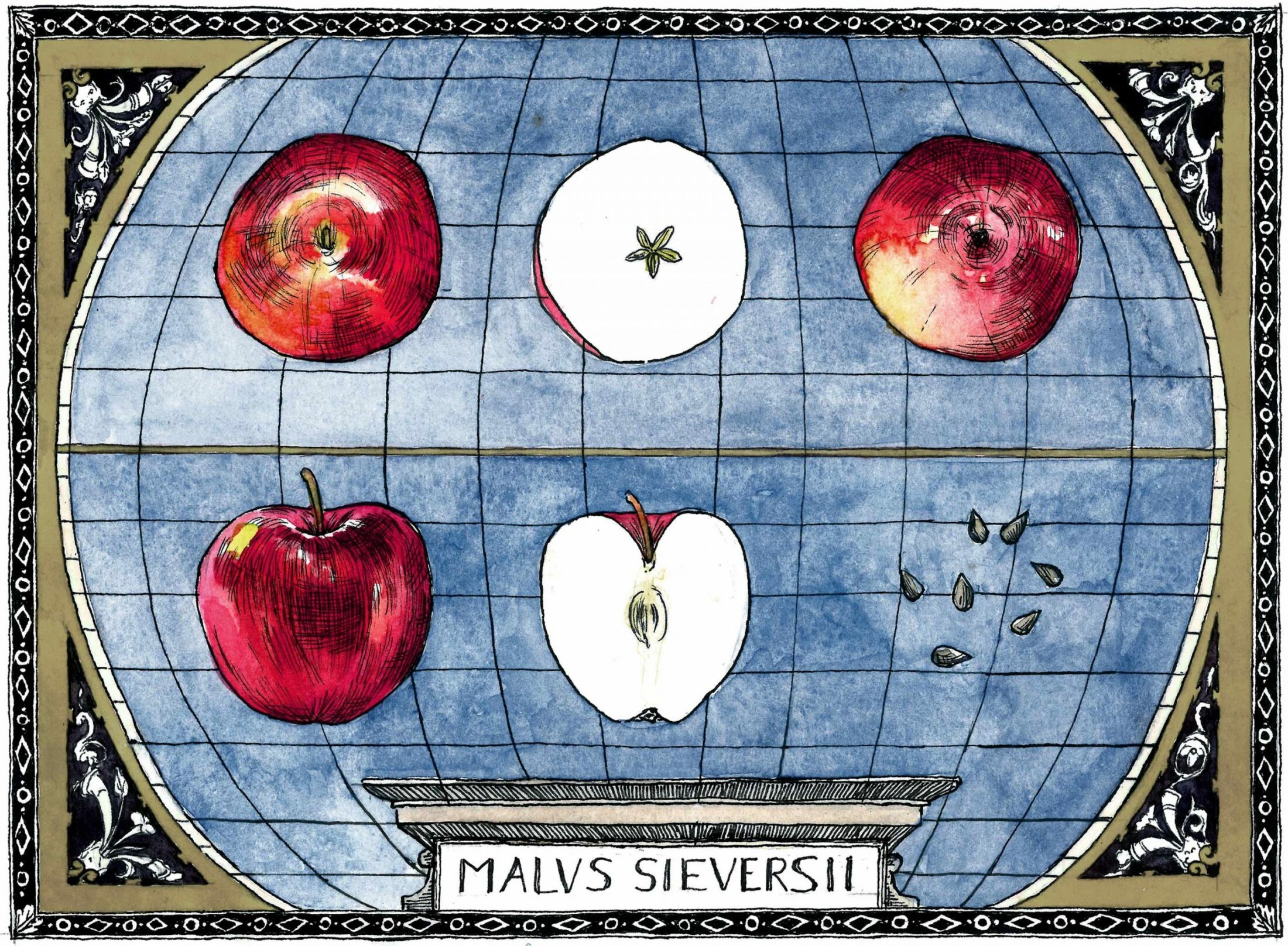

I am travelling to Kazakhstan, propelled by a story told to me by Barrie Juniper that is something between the Book of Genesis and the Just So Stories: How the Apple Began. Beside a black mulberry tree he planted thirty years ago outside the porters’ lodge at St Catherine’s College Oxford, I met Barrie, a don of the college, luminary of the Oxford Plant Sciences Department and apple guru. Ruby stains of the fallen mulberries smudged the paving stones. I had heard of Juniper’s pioneering work in tracking down the origins of the domestic apple to the Tien Shan Mountains of Kazakhstan and had come to sit at his feet and learn more. Over lunch, he outlined the long journey of the domestic apple from the wild fruit forests of the Tien Shan along the so-called Silk Road to the west. In the course of that journey, Juniper has discovered, the wild apple of the Tien Shan, Malus sieversus, evolved into the domestic apple, Malus domesticus, and eventually found its way to Britain with the Romans.

Barrie Juniper spent years searching for the ancestors of the domestic apple. He reckoned there were now some 20,000 varieties in the world including over 6,000 recorded in Britain. Many of the old varieties that haven’t died out altogether have become rarities, so Juniper realized that mapping out their genetic identities through DNA samples was a matter of urgency. In 1998 he travelled to Central Asia with some Oxford colleagues in search of the ur-apple. They went to Kazakhstan, to Alma-Ata, now known as Almaty. Alma-Ata is usually translated as ‘Father of all Apples’, although there is a school of thought in Kazakhstan that believes it is more accurately rendered as ‘Where the Apples Are’. It had taken Juniper over a year’s struggle with Kazakh official protocol to get permission to visit the outlying regions of the Tien Shan Mountains in search of wild apples, but eventually he and his companions set out from Almaty in the summer of 1998 under military escort to the remote mountain slopes known as the Djunguarian Alatau. Here they found forests of wild fruit: wild pears, plums, apricots, hawthorns, rowans and apples. The apples were all Malus sieversii, and their fruits varied enormously in size, shape and flavour, from the hard and the tart to apples that tasted and looked remarkably like our own familiar cultivated apples.

They collected apple specimens and took them home to Oxford, where they analysed their DNA and discovered that Malus sieversii shows a far closer affinity with the domestic apple than with any other wild species. But how could all the thousands of varieties of the domestic apple have descended from the wild fruit forests of the Tien Shan? To add to the mystery, Malus sieversii is reluctant to hybridize with other species. So how did all these variations on the theme of the eating apple arise? What makes the apple such a chameleon? The answer, in a word, is that apple trees are heterozygous. Plant the pips of a hundred apples from the same tree and the new generation of trees can differ, often dramatically, from their parents and from each other. This is how new kinds of apples have arisen by chance over the centuries: people taking a fancy to this or that new fruit, then propagating from that particular tree by taking cuttings from the shoots and grafting them on to other trees. All Bramley seedlings are descended from a single tree in someone’s back garden in Northampton. And so on, down thousands of years, so every single kind of eating apple in the world is a direct descendant of the apples that evolved in the forests of the Tien Shan.

After lunch, Barrie Juniper and I sat down in the fellows’ common room over coffee and the Times Atlas, which we opened at Central Asia. He began to explain how he thinks the domestic apple evolved; a story that ranged from the Yangtze Valley, to Neolithic Mesopotamia, to the orchards of Oxford. According to Juniper, Malus, the botanical family to which all apples belong, first evolved about twelve million years ago. To judge from the twenty-odd wild species that still exist in central and southern China, it probably bore a small fruit with hard but edible seeds not unlike those of its close relation, the rowan tree. The seeds would have been spread by birds. A small group of species penetrated north-west through the fertile country that is now Gansu Province into the area that was to become the Tien Shan Mountains as they arose in the same geological upheaval that created the Himalayas. Juniper believed that just one or possibly two of these ‘bird apple’ seeds was lifted over the rising hills to the Tien Shan and the valley of the Ili River, most likely in the crop or faeces of a migrating bird. The spread of the inhospitable Gobi Desert then prevented any migration of apple seed back to the east, and although they were walled in by glaciation to the west, the ice never reached these mountains.

In the foothills and valleys of the Tien Shan range, the new apple found itself in a genuine paradise. Bears, deer and wild pigs lived in the spreading woodlands, eating the wild fruit in autumn and selecting the sweeter, juicier apples while bees laboured in the pollination department of the same evolutionary project. The bears, living in the abundant caves of the Tien Shan, were avid fruit-eaters, and pips could pass through their guts unharmed to germinate in the dung. As Juniper pointed out, the baseball-glove claws of bears are perfectly suited to the grasping of apples. He had seen how enthusiastically they will vandalize a tree bearing a favourite sweet apple, dragging off whole branches in a kind of rough pruning. Out on the steppe, huge herds of wild horses and donkeys also browsed on the ripe apples and helped them spread westwards and south along the range towards what is now Almaty. Like the bears, they kept on selecting the larger, juicier, sweeter apples, so that as it spread west, the apple gradually became larger. At the same time this evolutionary pressure changed it from a ‘bird’ fruit with edible seeds to a ‘mammal’ fruit with poisonous seeds. The bitter taste of apple pips is cyanide, and the smooth, hard, teardrop seed coat evolved as the perfect streamlined vehicle to pass intact through an animal’s guts.

Juniper believed that by the time the ‘new’ apple had populated the northern slopes of the eastern Tien Shan and reached near Almaty, it had evolved into something like its present size and culinary appeal. Later, as human populations began to travel back and forth along the old animal migration routes between east and west, they helped to spread the new fruit. People call these routes ‘The Silk Roads’, but they were in use five or six thousand years before the discovery of silk, which lent its name to the route only during the period from ad 0 to 400. In the early days, said Juniper, camels would have been the means of transport along the routes, but, although they are as fond of apples as any other herbivore, their digestive system is so efficient that not even apple pips will survive it. Then, around 7,000 years ago, something momentous happened on the plains of Kazakhstan. The horse was domesticated, and soon started to travel the trading routes. The more direct northern trade routes led from Shanghai and Xian via Urumchi in north-west China to Almaty, Tashkent and Bokhara, then through Anatolia all the way to the Mediterranean coast. During winter the Tien Shan Mountains were impassable in the snow, so traders took the long way round to the south. But when the snows melted in July, the caravans turned north and until the first snows in November travelled through the Ili Valley and the Tien Shan range via Almaty, passing through fruit forests on the way.

Thanks to the relatively inefficient digestive system of the horse, the seeds of apples pass through the gut unharmed, so horses were very effective disseminators of a random variety of seedlings that grew up into flowering trees that, in turn, were naturally pollinated into yet greater permutations of genes and fruiting characteristics. Apples would also have been a highly portable source of food for both horses and traders, and must surely have travelled many hundreds of miles stashed in saddlebags. By the time the Romans introduced the domestic apple to Britain, they had learnt the secret of grafting.

Barrie Juniper chanced on the early origins of grafting while riding his bicycle through Oxford one afternoon. He met Dr Stephanie Dalley, an orientalist, who told him about something she had seen on the wooden cuneiform tablets she was translating. They were 3,800 years old and had been discovered at Mari, on the banks of the Euphrates in Syria. Some of them depicted the grafting of vines in the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates, where the Babylonians are known to have experienced the problem of soil made salty through irrigation. The tablets revealed that by that time gardeners and orchardists knew how to graft grapes on to salt-tolerant rootstock. If they could graft grapes, they could almost certainly graft apples too.

A favoured apple tree could be reliably propagated only by cutting scions from it and grafting them. Scions could be preserved and carried by driving the ends of the stems into a hard fruit such as a quince. Thus, the favoured fruit variety could be transported west and reared in the orchards of Babylon, and later in Greece, then Rome and eventually in Britain.

In his biography of Alexander the Great, Robin Lane-Fox describes how the enterprising general took gardeners skilled in grafting from the Tigris basin home to Greece, and is known from written accounts to have trained his soldiers to fight in naval exercises in which apples were fired in broadsides as ‘blanks’. The Romans learnt to cultivate the apple from the Greeks and eventually brought it to Britain. At St Romain en Gal in the South of France, a Roman mosaic shows the progress of the apple year, from its grafting to its harvesting. The Romans grafted Malus sieversii on to the wild Malus sylvestris so that the bottom half of the tree could eventually be utilized as the ideal timber for making the cogs of waterwheels or windmills. Barrie believed the Saxons must have inherited the relict orchards of sweet Roman apples and named many places after them. He has found at least forty-seven apple place names: towns and villages such as Appleby and Appledore. The Celtic prefix af or av also signifies ‘apple’, as in Avalon or Avignon.

Trees are everywhere, wonderfully unkempt and wild-looking.

Barrie thought I was mad even to consider reaching the Tien Shan Mountains of Kazakhstan or Kyrgyzstan without months of preparation and frankly warned me that in the face of the endless protocol entailed in securing visas and permission to visit the mountains, I would probably give up. He and his Oxford colleagues had written over 200 emails and letters in their original quest to reach the Tien Shan fruit forests. He was very nearly right. There were times when I almost did give up, as I cycled across London to the Kazakh Consulate opposite the V&A in Kensington again and again, or sat waiting there in queues in an airless office at the bottom of the basement stairs hoping for my elusive visa.

But finally there I was, flying into Almaty at two in the morning to meet Luisa, Barrie Juniper’s friend and interpreter. Luisa is learning to drive and has taken a lesson on the way out to the airport with her instructor, Johnny, who drives us back into town at breakneck speed in his Lada along wide, empty boulevards of limes with whitewashed trunks. Outside the wine factory, topiarists have sculpted the limes into giant bottles. Kazakhs, I later discover, love topiary and never pass up an opportunity to flex the shears on almost any tree. On Republic Square, outside the old House of Government building, stands a row of Central Asian elms, shaped into perfect domes like a row of soldiers in dark-green busbies. Everywhere you go in Almaty there are trees and tree-shaped fountains.

Johnny’s Lada is dwarfed by the great sweeping forecourt of the Almaty Hotel. So is my singularly tatty rucksack, which a porter insists on carrying in without a trace of irony. The Almaty is a huge old-style Soviet hotel opposite the Opera with tiers of balconies like the decks of an ocean liner. By some miracle worked by Luisa on the unsmiling receptionists, I get a room three floors up, wonderfully tatty, complete with plugless bathroom, jammed balcony French window, TV, broken fridge, and large desk. We arrange to meet in the morning, and I fall asleep instantly.

I wake to sunlight and traffic and the brilliant surprise of the snowy tops of the Tien Shan Mountains, the Heavenly Mountains, that form the steep backdrop to the city to the south. The sun breaks over the ridge, casting a pale duck-egg shade on the snow in the topmost combs. Everything in the backlit city is silhouetted and dramatic. People move along the streets like shadow puppets. The air smells fresh and cool. The city itself is steeply raked up the mountainside, rising from two to three thousand feet in the straight lines of its original Soviet grid, with the 15,000-foot mountain wall behind. My first impression is of a Ruritanian city built in a forest: trees are everywhere, wonderfully unkempt and wild-looking, shading the streets and parks, fed by the mountain rivers and streams that race through the city.

During the 1870s and 1880s, when the place was still called Alma-Ata and the city was being planned by the Russians, the city engineer, a German by the name of Baum, stipulated that every citizen must plant five trees in front of his house. The scheme was such a roaring success that there are now some 138 different species of tree in Almaty. Baum is of course ‘tree’ in German. Mr Tree was particularly active in the leafy district of the city known as Kompot, which means ‘fruit salad’, and it was probably Baum’s idea that every street there should be named after a fruit tree. Plum Street, Cherry Lane and Apricot Gardens are no more eccentric than our own Birdcage Walk or Petticoat Lane. Many of the Almaty streets are shaded by ramshackle avenues of magnificent oaks in the prime of life, no doubt once twinklings in the eye of Baum, or acorns in his pocket. There are fine apple orchards all over the city, as well as the wild apple woods on the slopes of the Alatau Mountains that rise like a wall behind it. You can sometimes go up there in winter, apparently, and find apples buried under the snow, perfectly preserved by the layer of autumn leaves beneath.

Outside in the wide expanse of the Republiky Alangy, a wedding party is assembled on the steps of the Monument to Independence in bright sunshine. A little folk-band with an accordion, a two-stringed dombra and a drum like an Irish bodrun plays Kazakh tunes. Some of the wedding guests dance together, while others pose for photographs, all dressed to the nines in suits and ties or bright dresses. Luisa flags down another Lada, and we race to meet the Director of the Almaty Botanical Gardens and distinguished member of the Kazakhstan Academy of Sciences, Professor Isa Omarovich Baitulin. Lunching together on borsch and tea, we make plans for a visit the next day to the wild apple forests of the Talgar Valley, some thirty miles to the east of Almaty. After so much preparation and difficulty, I can hardly believe this is happening. Isa cuts a magnificently handsome figure with the oval face, high cheekbones, narrow eyes and olive skin of the Mongol Kazakhs. To our amazement, this fit and agile man turns out to be in his eighties. But he has spent much of his life outdoors, studying the fungi that live in close association with the roots of trees.

Isa speaks little English and I feel ashamed of my small Russian and no Kazakh, but we find we can converse quite happily through Luisa, or in the botanical Latin of the names of trees and plants. Isa says this is a good time to walk in the wild fruit forests because the harvest is not over, and much of the wild fruit will still be on the trees. At the end of May, he says, the whole mountain is white with so much blossom it could be snow. There are wild apricots, blackcurrants, raspberries and mulberries in the fruit forests too, and in the south of Kazakhstan wild woods full of walnuts and pistachios. The wild apples follow the valleys, growing at a height of 3,000–4,000 feet. In Almaty, he says, we are already at 2,800 feet and the Jungar Alatau Mountains behind us rise to 16,000 feet. He talks about the great Soviet scientist Nicolay Vavilov, who was the first to suspect that the original ancestors of all domestic apples lived on the Tien Shan Mountains and in 1936–7 led the first botanical expedition into the wild fruit forests. Vavilov felt sure the domestic apple was descended exclusively from Malus sieversus, the wild apple of the Tien Shan, but without the modern genetic techniques of DNA profiling he was unable to prove his hypothesis, as Barrie Juniper did some sixty years later. By the end of lunch we have all relaxed after our initial formality and arrange that Isa will come with a Russian jeep in the morning and we shall set off for the wild fruit forests.

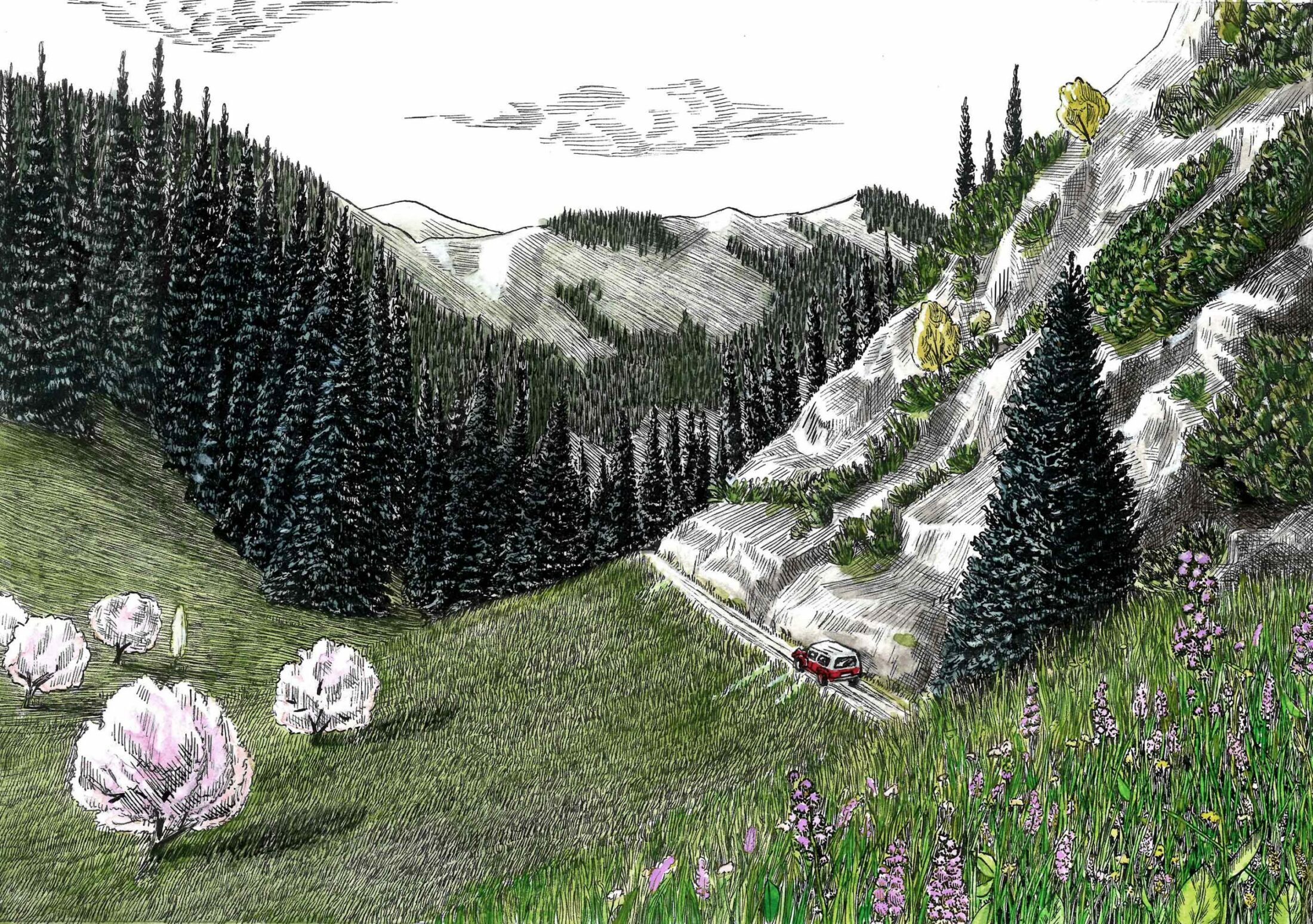

Five of us pile into Ali Khan’s red Russian jeep in brilliant early sunshine and set off for the Talgar Valley and its wild fruit forests. Our route runs via Talgar, a large village in the hills about forty miles south-east of Almaty. In 1936 Fitzroy Maclean, whose book Eastern Approaches had informed my own journey, travelled exactly the same way on his first excursion out of Almaty, finding a place on a lorry heading out of the city. On reaching Talgar, he set off into the hills on foot, followed by the NKVD secret service agents who tailed him everywhere, but they were local men, and Maclean ended up being entertained to lunch with them in a peasant cottage in the hills.

Ali Khan, our driver, is Isa’s son and a judge, although apparently he’s resting just at the moment, busy trying to start up a tourist agency for visiting scientists. Isa Baitulin has invited Dr Kuralay Karibaia, a jolly, brown-haired woman dressed in jeans and a red-and-black baseball jacket. Kuralay manages a United Nations Global Ecology Fund project to conserve the fruit forests.

Ahead of us are the snowy peaks of the Zaeleiskoe Alatau and the 16,500-foot Mount Talgar. The jeep is a Yaz with a canvas roof and very hard springs. There are no seat belts, only a handle on the dashboard to grip. They all insist on giving me pride of place in the front seat, but in all honesty I would rather be in the back where it is marginally safer, and where Isa, Luisa and Kuralay sit squeezed together. After a mile or two we are all covered in dust. We bump along wide, dusty roads lined with the whitewashed trunks of poplars or oaks, zigzagging to avoid the vast potholes.

Soon we’re in the suburbs, jogging past single-storey cottages with bright wooden windows, pine-boarded or cob walls, shallow-pitched tin or felted roofs, and little balconies and porches raised on wooden stilts. The walls are mostly ochre and the doors and windows bright blue, and all have orchard gardens bursting with lush, fruiting trees, mostly apples and pears but also apricots and walnuts. Along the verges, we see little kitchen tables and chairs set out with jam jars of wild fungi, milk or honey for sale. Others display such curious combinations as a packet of cigarettes, a melon or two and a bottle of lemonade; petrol or motor oil and a clutch of potatoes. A girl squats in the shade of a poplar beside a neat heap of melons. Another sells besoms of bark-bound brushwood. There are bucketfuls of apples and baskets of tomatoes, onions, gourds and pumpkins beside every whitewashed tree.

We are by now on the open steppe, bowling along the very same route taken by Fitzroy Maclean on his first, covert, journey to Almaty in 1936, in the days of the Soviet Empire. Beyond the avenues of roadside trees, Kazakh horsemen are herding their cattle, some of them tiny dots on the distant plains of endless brown grass and dust. Dogs and foals run across the steppe. Lively streams skirt the road on either side, and in the foreground are commercial apple orchards of oft-pruned trees no one has got round to replacing. Isa calls them middle aged. Cattle graze beneath the apples while their cowhands stretch out in the shade and sleep. We pass a man wheeling a slopping milk churn on wheels. A transhumant bee-keeper’s caravan full of hives ready to be towed up by tractor into the forest is parked by a barn.

At Talgar, a large village in Maclean’s time and by now almost a little town, we weave through lanes of baked mud surrounded by ochre walls and blue windows, an escort of terriers and mongrels prancing round the jeep. Then we swing in through the high gates of the Forestry Headquarters and find ourselves in a yard full of huge logging trucks and more dogs which rouse themselves from under them to come to meet us. The five old bull-nosed Russian Army lorries are endowed with every conceivable winch, crane and towing device, and their wheels are taller than a man. The two head foresters emerge from the office in suits and ties, and there are formal introductions, watched by an old baboushka in the caretaker’s gatehouse, her bed just visible behind the door. The Chief Forester is introduced as Medeo.

The foresters clamber into their jeep and lead the way out of Talgar, thundering uphill past an open-air bazaar where more lorries are unloading potatoes and onions. Along the dirt road into the foothills, every rubbish heap grows a crop of pale-blue chicory. I am in that bemused state when you no longer comprehend what exactly is going on but quite happily luxuriate in the sheer richness of everything, the sounds of Kazakh and Russian, the rose-capped mountains, the bustling villages, the shadows of poplars, as you would in a dream. We splash through a river bed and pass a lovely old wooden village mosque, like a village hall with a gleaming silver minaret atop its roof. We catch the rich smell of woodsmoke and baking bread as we drive by farms with blackened cob ovens in the yards sheltered by stilted tin roofs. We traverse the foothills through orchards, planted by the Soviets, laden with ripe pink apples. We go pitching and rolling over the rounded foothills into the minor valleys of mountain streams, lurching through the fords, charging straight back up the next hill. I notice that the handle I’m clutching on the dashboard is the one part of the well-painted Yaz that is worn completely smooth to the bare steel.

Stopping to admire an orchard, Kuralay jumps up to pull down a branch, and we scrump an apple or two. This is exactly what Maclean did when he passed this way in the thirties. Climbing and winding our way through hamlets and farms, we press on, past a garden shed like a tiny mosque with a roof of beaten tin that was perhaps once an oil drum, past marigolds in every cottage garden and the magnificent bulging torsos of cob-built bread ovens, their skin toasted and fissured, the fresh loaves laid out to cool on their roofs like sleeping cats. The fierce, high fences round every little farmstead, and the dogs chained in the yards to dead hulks of cars that serve as garden sheds and kennels, set me wondering about the intriguing bandits in the hills that people have mentioned now and then. We pass a tractor with a whole family crammed in the tiny cab, a small boy somehow perched above the steering wheel and a beaming farmer behind it.

Our sticky mouths and fingers stained orange and purple, we dip and thread our way through the fruit forest.

My ears pop as we climb higher, and the air feels much cooler. We breast the top of a ridge and suddenly there they are before us: the wild apple woods. The whole of the mountainside we are approaching is covered in them, beginning with an open, wild wood pasture that shades by degrees into the dense forest that runs on up the slopes. Curiously, it feels like country I have always known. I feel excited, of course, yet entirely at home and at one with the landscape. I have the odd feeling I have lived here all my life. At first we pass through wild savannah scattered with groups of tall apple trees or single specimens, their complex multiple trunks twisted together like sinews. The trees are all thirty to fifty feet tall, spreading and unpruned, except here and there by animals, still bearing plenty of fruit in a good year. They cast sharp shadows across the dazzling yellow grasses of the meadows. One of the trees is massive, its branches apparently full of fruit, but as I approach closer I realize I am not seeing apples but yellowing autumn leaves caught in glancing sunlight. The bark is worn smooth by the hides of cattle and horses. Wisps of their hair stand out like implants. The wild apples flock more densely around the slight valleys of the hundreds of streams that run off the mountains and irrigate the meadows. We are high up, the sky is very blue, and the air smells very clean and thin. To the south is the wall of the Heavenly Mountains, and if I face the other way all I see for hundreds, even thousands of miles is pale-brown steppe with low, rocky hills in the foreground.

After rattling across several miles of this high savannah we pull up before a mound of wooden beehives, an old Mercedes van and a curvaceous, wood-framed caravan sheathed in sheet steel that could have come straight out of La Strada. I fully expect to see Anthony Quinn ease himself out of it, yawning and stretching in long johns and a buttoned vest after a strenuous night. And I am not disappointed. It is Valery who comes out, looking every inch as good, his eyes slitted against years of steppe and desert sun, shining brown skin stretched over the high cheekbones, his face benevolently lined. He is probably still in his thirties, but so weathered, skinny and obviously tough that I felt he would always look the same. He wears the soft black suede boots of the horseman, skilfully made from a single piece of hide, stretching over his calves, trousers tucked in a touch rakishly, and a black V-neck T-shirt. He keeps a dozen big rabbits grazing in a run, a few goats and a small flock of sheep. Some chickens emerge from under the van as we talk and resume their pecking about. Valery shows us the wild flowers on the meadow that feed his bees. In spring the hills are ablaze with wild tulips, but in the dust of autumn all we see is the pale blue chicory. Valery has sixty-seven hives, each yielding some ten to twelve gallons of honey each year. He says he produces about a ton of honey from every fifty hives. Each colony will have consumed about 265 pounds of honey for itself over the year: the ten or twelve gallons are what is left over. By feeding sugar to the bees, you can take more of their honey, but that is not generally Valery’s way. In the height of summer, there will be over a thousand beehives scattered about these hillsides, the bees feeding off the wild herbs and in the fruit forests.

I wonder if Valery has a wife, and what he does for comforts. He clearly likes the life, and says so. He says the Talgar hills have their own completely different climate. In winter there can be three feet of snow for weeks. In Almaty it can be five below zero and here it may be a warm 20 degrees. We are a bit of a delegation, and it feels wrong to ask him too many personal questions: we’re intruding on a peaceful, almost monastic life in one of the most beautiful places on earth. In spring, says Valery, there’s an explosion of bees and flowers. These saffron meadows burst into flame with tulips, and the hills are a huge snowfield of wild apple, apricot and hawthorn blossom.

I’m sad to leave the solitary Valery, whom I instinctively like. When we shake hands, it is the two-handed lingering double-clasp kind with a deep look into the eye. The look says, ‘We come from vast distances apart on this earth, yet I feel a natural, spontaneous respect for you. It is very moving, that we far-flung people from different tribes are clearly first natural friends, not enemies at all.’ I very nearly catch myself making the little speech, but restrain myself in time. Luisa and I buy a litre jar of Valery’s best wild apple-blossom honey to share. When Valery hands it over, it feels like a blessing—the palpable proof of the goodness and beauty of the place, and the wild apples. I experience the same feeling when I look around the faces of my new friends: the first thing I see in them is their beauty, and I rejoice in the diversity of human genes that made them, as the flower genes seeking each other in the pollen made the honey.

Further on through the woods, we stop by a little clearing and pick sweet hawthorn berries the size of fingertips. Unlike their English counterparts in the same Crataegus family, they are sweet, but you still have to spit out the hard pips. Isa and Kuralay then turn their attention to a dense relict grove of cultivated blackcurrants, a giant variety from China lacking the toothy tartness of our native currant but a welcome addition to our gastronomic wildwood tour.

Our sticky mouths and fingers stained orange and purple, we dip and thread our way through the fruit forest, past a solitary yurt in a wooded glade, then two or three tented settlements or simple farmsteads. Outside a very simple wooden hut, barely more than four or five packing cases slung together, sit a little family with their horses and cattle tethered near by. Two small girls are braiding their mother’s waist-length hair, proudly brushing it for her as it shines in the sun. Climbing a steep holloway past exposed roots of elms, apples and apricots, we come to a cottage and farmstead in the woods. Here, says Isa with a little bow, we are invited by the foresters to lunch.

The cottage is set deep in the fruit forest. Leaves and branches arch together overhead, so the place is cool and dappled. We go in up open steps of pine and through a wooden porch raised to the floor level of the house on stilts. Each of us pauses at the foot of the steps to wash our hands at a little cistern contraption supported on a post driven into the ground, with a basin beneath. I was to become familiar with these elegant, water-saving devices wherever I travelled in the countryside across Central Asia. The steel cylinder, shaped like a miniature samovar, holds two or three litres; you punch a piston plug upwards with the back of one of your hands to let the water down as you wash them. It is like milking a cow. A soap dish and hand towel also hang from the post.

We all step out of our shoes in the porch and leave them there with dozens of others belonging to the household. The custom reminds me of my prep school, where we each had our own shoe bag hanging from a peg in the cloakroom, and changed into ‘house shoes’ for lessons. Padding about in stockinged feet on the fine carpets spread over the wooden floors everywhere feels at once more intimate and informal. A serious-looking woman in a long red skirt and green silk headscarf ushers us into a room at a corner of the house: it contains a bed along the innermost wall, pine-boarded walls and a floor adorned with rugs, some felted in bold, zigzagging Kazakh designs. A large, low table occupies most of the remaining floor space except for a great many cushions and a samovar by the fireplace, tended by the wife and daughter of Medeo, the forester whose house this is. The women silently take turns at squatting beside the samovar and dispensing a continuous supply of chai.

The table is spread with a spectacular array of dishes of all colours: bowls of kymys, the fermented milk of mares, sour milk, bowls of wild mushrooms of two or three kinds, sliced tomatoes and cucumbers. We seat ourselves on the floor, cross-legged with our backs against the wall along two sides, wedged and propped by cushions. Isa sits at the head as the senior man, and I sit at his left hand as the principal guest. Medeo sits to the right of Isa, Luisa next to me, then Kuralay, then all the women of the house and two more foresters. The cottage, we learn, is called Saimasai, meaning ‘Stream in the Little Valley’.

Our lunch begins with a prayer by Isa. It is long and involved and seems rather more than simply grace. We sit with our hands cupped open, as if to receive heavenly food. Then chai is poured, sour milk added, and passed around. Isa proposes we drink vodka, wine or brandy. Luisa and I both choose wine and taste the fruity, full-bodied red Kazakhstanskaya. First we eat lamb shashlik in tender strips with a dried, hard cow cheese and bread, and savoury doughnuts that we dunk in sour milk.

Now come the toasts, proposed by each of us in turn in the true filibustering tradition of an oral nomad culture, Luisa gallantly translating, and abridging, the sentiments so eloquently expressed. Isa goes first, with a rousing speech about the glories of Mother Nature that ends with the sentiment, endorsed by all present, that ‘to work for Nature is a noble endeavour that knows no boundaries. Nor should it, for it is our common purpose to work for the ecology of our world.’ As glasses are refilled all round, Kuralay rises to deliver another long and lyrical paean to Nature, culminating with the assertion that ‘nature’s bounty is very great and we all owe it to her to work ceaselessly on behalf of diversity and its expression in the natural world.’ We could, I feel, all have been sitting round at some Gaia conference at Dartington or Findhorn.

Now it is my turn. Topping up my glass for courage, I speak of Kazakhstan’s two great gifts to the world: the cultivated apple and the tamed horse. However, I say with a flourish, I have today discovered a third: the best hospitality in the world. And so it goes on, with more toasts, and yet more elaborate and sincere compliments, all expressed in the declamatory tones of a bard reciting an epic poem. Since the Kazakhs are the proud possessors of a great tradition of oral poetry, passed on by the bards, or akyns, in competitive recitals known as aiytis, it is not surprising that oratory seemed to come quite naturally to those present.

After all this high drama, Isa declares an interval, during which we will take the afternoon air outdoors, work up more appetite, dream up more toasts and await the presentation of the next course or two. Kuralay sets off into the woods on horseback and returns like a bee to the hive with saddlebags full of wild apples. I wander up a steep path and sample some sweet feral fruit, slipping the apple pips into my trouser pocket for later planting in Suffolk. Buzzards mew somewhere above the trees, and horses graze, tethered, under the shade of an orchard.

To work for Nature is a noble endeavour that knows no boundaries.

Back at the cottage, I sketch the outdoor summer kitchen, a Central Asian institution I am to encounter everywhere I go. Such places never fail to bring out the untutored architect in me, and I can’t help dreaming of constructing some variation on the theme. Let loose on a personal garden city like Letchworth, Welwyn or Hampstead Garden Suburb, I would end up with something between a shanty town and an allotment. Cooking al fresco in an open-sided kitchen built in the garden close to the vegetables and compost heap, with its own wood-fired ovens, charcoal grill and range of sinks draining straight into an irrigation system growing melons, courgettes and gourds, seems to me a fine idea. Set apart from the house, the summer kitchen keeps all the smoke and cooking smells away from it, and allows the space and ventilation to spit-roast a whole lamb over a glowing, open fire, as the women and girls are busy doing now, or to bake quantities of bread in the splendid clay oven. Smoke billows out of the cob chimney as the women in headscarves and floral skirts and children in embroidered pillbox hats bustle about preparing and cooking the forthcoming courses.

The shallow-ridged tin roof of the summer kitchen covers the cob-built ramifications of oven, bakery and grill, and extends forward over a raised wooden working deck to form a veranda with three elegant arches of coppiced hazel that must have been bent and secured when still green. Balcony rails of hazel also run along the front of the kitchen, with wooden steps to its entrance and a wicket gate to keep the dogs out. I watch humming-bird hawk moths play round the marigolds in a flower bed in front. All the building materials for this little palace except the reused corrugated tin on its roof are local, simply dug up or cut down in coppice woods that will soon grow back again.

Just across the garden from the summer kitchen is the sauna, another half-cob, half-wooden shed, heated by a wood-stove with a water tank perched above it. In its cool, shadowy, whitewashed interior I find a bench on which to sit naked in the steamy heat, a plastic bowl and mug, a large jug and a bunch of leafy oak twigs for the traditional mild self-flagellation. Here again, the drainage pipe runs off conveniently into an irrigation trench in the vegetable garden.

An hour or so later, the lamb is served. It has been slaughtered specially for our visit, as is the custom. At the head of the table, Isa carves the head, deftly dissecting and sharing out the various symbolic organs. First, the ears for the children, ‘that they may listen carefully and hear well in the forest’. Then the tender cheeks for the women, and the eyes for the two most senior foresters, to help keep them watchful for approaching dangers. I wonder what I might get, and am rewarded with a scallop of pinkness from just above the forehead, which they all assure me is the seat of the imagination. As head man, and perhaps as a professor, Isa spoons himself a liberal helping of the brains, then carves us all huge portions of the rest of the beast, including the greatly relished fat from around the tail. Kazakhs have a liking for fat-bottomed sheep, bred for the rump of fat either side of the tail.

We now add to our plates portions of a kind of pasta to make beshbarmak, which roughly translates as ‘five fingers’ because the dish is traditionally eaten by hand. Isa also insists I accept the choice globules of prized fat from around the sheep’s ample bottom. More wine ensues, with a magnificent forest fruit salad, honey, fresh green walnuts, melon, cakes, more chai, and further, supplementary toasts and votes of thanks. Then, abruptly, Isa says grace and the meal is over, with many a double handshake and invitation to return as we all line up outside for a group photograph, then clamber back in the jeep and bounce away downhill in our swarming cloud of dust.

The Memory-Tree

A Postscript by Robert Macfarlane

Grief, like an apple tree, grows crooked not straight.

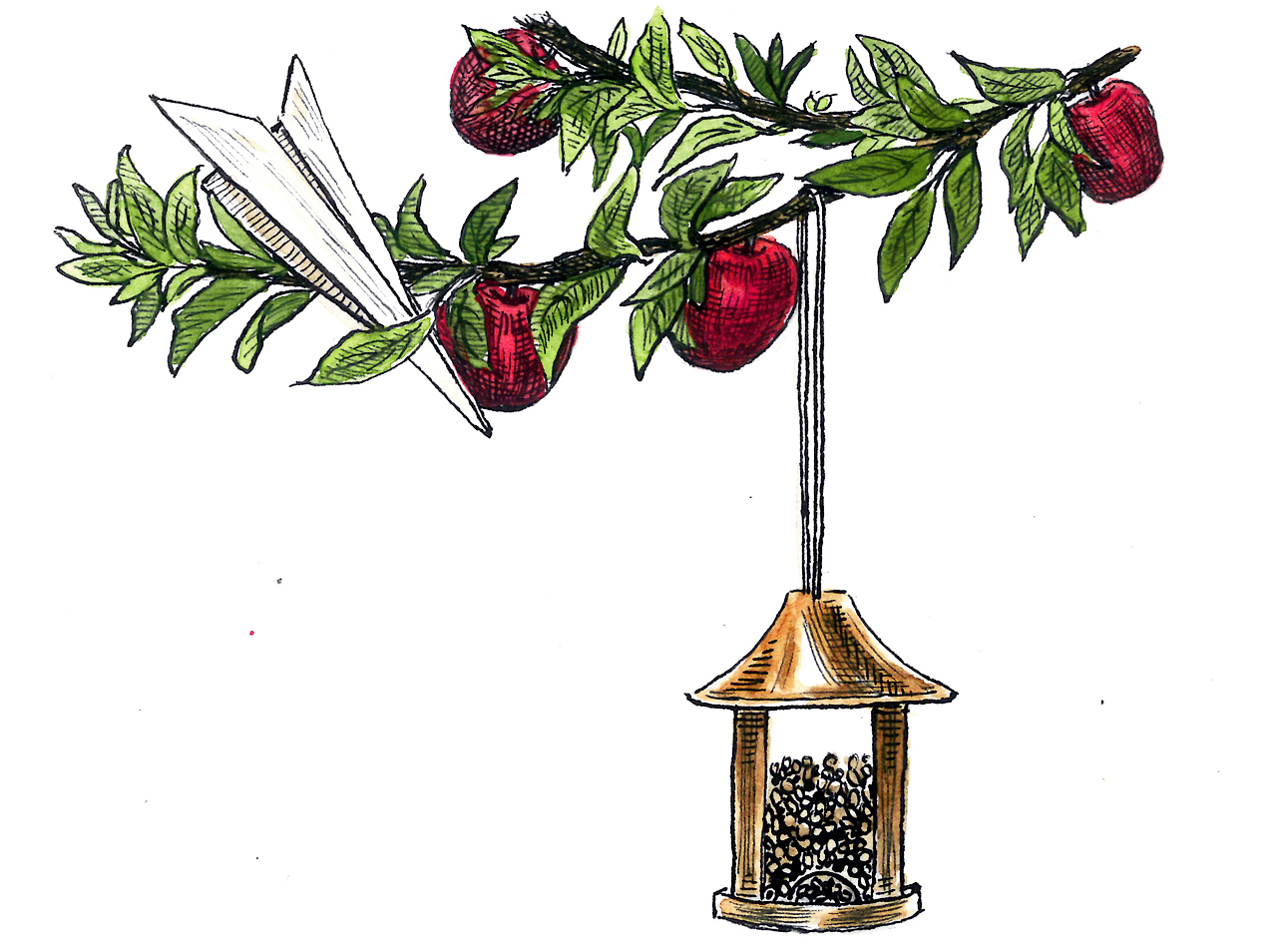

It took me years to find it, but tucked away in a paragraph of “East to Eden” was a sentence that would grow through my own life in ways which are still surprising me now, more than a dozen years on. It comes after Roger has enjoyed a lunch of kymys (fermented mare’s milk), red wine, mushrooms, and grilled lamb with a family of Kazakh woods-people, up among the wild apple forests of the lower Tien Shan. Once the meal is ended, Roger steps outside. “I wander up a steep path,” he writes, “and sample some sweet feral fruit, slipping the apple pips into my trouser pocket for later planting in Suffolk.”

That “sweet feral fruit” belonged to the ur-apple, Malus sieversii, thought to be the wild ancestor of all domesticated apples (Malus domestica). And Roger did bring those pocketed pips—scores of them—back home to England, carefully packed with damp cotton-wool into three 35mm black plastic film canisters. He brought the pips home, he stratified them, he planted them in pots filled with good, moist soil, and—for apple pips are notoriously difficult to germinate—twenty or so of them sprouted; and perhaps thirteen or so of those became seedlings, which he lined up on a windowsill at Walnut Tree Farm where they gangled and tangled and yearned for the sun.

Then Roger died—and the seedlings nearly died too. Pot-bound and under-watered during his illness, it was only due to luck and hardihood that they survived. Sometime in the spring of 2007, around the time that Wildwood was published, the seedlings were spotted, identified, re-potted, and given light by Titus and Jasmin Rowlandson, two young friends of Roger’s who had moved into Walnut Tree Farm after his death. The ur-apple seedlings flourished into ur-apple saplings, and in due course ten of those saplings were planted out by Titus in two rows, set in a stretch of field behind a steep-eaved black-timbered barn that Roger had raised himself years previously.

And Jasmin gave one of the two or three remaining saplings to me. I put it on the front seat in its pot, strapped it in with a seatbelt, checked that the passenger-side airbag was enabled, and drove home, feeling strongly—ludicrously—as if Roger were there beside me. That weekend I planted the sapling in the chalky clay of my modest city garden. From the wild fruit forests of the lower Tien Shan to a 1940s estate-house in suburban south Cambridge, this ur-apple had made a strange, long migration.

Grief, like an apple tree, grows crooked not straight. There have been times in the years since Roger’s death when I’ve missed him with a burning, cutting want. Periods, too, when his absence has felt oddly accommodating, like a flattened patch of undergrowth made comfortable by turning and turning about. Through all of that time, the ur-apple has got taller, adding growth-rings to the invisible year-clock it keeps within its trunk. Each spring, when it leafs into a green goblet, it surprises me with its new volume. Though it is commonly known in our family as “Roger’s tree,” we treat it not with reverence but with friendship and familiarity. My three children have hung baubles from it and got paper aeroplanes lodged in its branches; it is used to suspend birdseed-feeders that get maddeningly plundered by squirrels rather than goldfinches—and whenever we bring seaside pebbles back from a summer beach holiday to Wales or Devon, they get put around the base of the tree’s trunk, both as cheery votive offering and as weed-suppressant.

Despite—or perhaps because of—this easy kinship, there are moments when the ur-apple feels keenly and simply to me like my friend; like Roger. A few times each year I find myself un-self-consciously talking to it as if I am talking to Roger: asking advice, wondering something aloud, telling him a story. And a few times each year, more mysteriously, the tree causes both memories and new thoughts to grow without warning in my mind, like an apple suddenly fruiting from bud to ripeness in an impossible second. I recently read Seamus Heaney’s translation of Rilke’s poem “The Apple Orchard” and found that its opening line described an “inner” fructification I recognised instantly:

From feeling and from feeling recollected,

From new hope and half-forgotten joys,

And from an inner dark infused with these,

Issues in thoughts as ripe as windfalls scattered

Here under trees like trees in a Dürer woodcut—2

Horticulturally speaking, apple trees that are grown from seed are rarely true to type. That is to say, they are self-unfruitful; their flowers will require pollination from another nearby apple tree for a good fruit set to occur, and the seeds of any ensuing apples will be a genetic cross between the parent tree and the pollinating tree. Apple trees grown from seed also take longer to reach fruiting maturity than those which are grown from a graft of scion wood onto rootstock; between seven and twelve years, or even more, depending on conditions.

For seven years, my ur-apple did not even blossom. It leafed gorgeously each spring—but it would not flower. I pruned it and fed it with care each winter, and each April felt a pang of disappointment, tending toward reproach, at the absence of blossom. Then in the spring of 2015, I published an essay about the afterlives of Roger’s remarkable books. “A life lived as variously as Roger’s, and evoked in writing as powerful as his,” I wrote there,

means that even after death his influence continues to flow outwards […]. Though Roger is gone, many of his readers still feel a need to express […] the connection they felt with his work and world-view, and so they still write letters to him, as if he might somehow read them. As I am Roger’s literary executor, and as our writings have become intertwined, many of these letters find their way to me. They come from all over the world, and from various kinds of people: a professional surfer from Australia, a Canadian academic, an older woman from Exeter confined to her house due to mobility problems, a young man re-swimming the route of Waterlog, lake by lake and river by river, in an attempt to recover from depression […]. Green Man-like, Roger appears in unexpected places, speaking in leaves …

Two months later, the ur-apple burst into leaf, a month later it burst into pink-white blossom, and over the summer some of those flowers set fruit. In early autumn I harvested the dozen or so small, glowing apples that had appeared on the tree, and from that “sweet feral fruit” I gathered the forty or fifty pips they held. It did not matter to me that these were unlikely to be genetically identical to the ur-apple; indeed, I felt that this blurring brought its own variegated beauty to the new fruit, much as Roger’s writing had mingled with the minds and hearts of his readers around the world.

That same autumn I read the poet Michael Hamburger’s elegy to his friend Ted Hughes. Hamburger had fled Nazi Germany in 1933 as a child, seen action in World War II, and settled eventually in Suffolk, not far from Roger. There he became friends with a fellow German emigrant, W. G. Sebald (Hamburger appears in Sebald’s masterpiece, Die Ringe des Saturn / The Rings of Saturn), and cultivated an apple orchard, becoming notably expert in coaxing obscure apple varieties to grow successfully from seed rather than from graft. Among the trees in Hamburger’s orchard was one risen from a pip given to him by the poet Ted Hughes from a tree in Hughes’s beloved Devon. On 29 October 1998—the day after Hughes’s death, and deep in the English apple season—Hamburger wrote a roaming elegy for his friend that concluded back among the trees of his orchard:

Uneaten this day of his death

In either light the dark Devonshire apples lie

That from seed I raised on a harsher coast

In remembrance of him and his garden.

Difference filled out the trees,

Hardened, mellowed the fruit to outlast our days.3

I was moved and fascinated by Hamburger’s doubled notion of fruit “outlast[ing] our days,” and of “difference fill[ing] out the trees.” Reading his elegy, it became clear to me that I should give away the pips I had harvested from Roger’s ur-apple. So I parceled up four or five pips at a time in damp cotton-wool, sealed the cotton-wool in small bags, and then posted or gave the bags to ten or so people—to Roger’s editor at the time of his death, who had published Wildwood; to friends who I knew still missed him; to certain readers who I knew had never met him but for whom his writing had become indispensable; and to his two translators, Andreas and Frank, who had grafted Wildwood into German.

My gift of the pips came with only one obligation. If any of the recipients did manage to grow the pips into seedlings, then saplings, then at last into fruiting trees, then when the first crop of apples came on those trees—a dozen or so years into the future—they should gather that fruit, harvest its pips, and give those pips to people who they knew loved Roger’s writing; and that when they gave those pips on, they should accompany the gift with the same single obligation as the one to which I had made them subject. In this way, it seemed to me, much as Roger’s work had grown and branched since his death, so this action might slowly create a worldwide wildwood of memory-trees—a dispersed forest of ur-apples, spreading out from those first pips harvested by Roger on a steep Tien Shan hillside in the autumn of 2003, drowsy after a good lunch, somewhere east of Eden.

- WILDWOOD: A Journey Through Trees by Roger Deakin. Copyright © 2007 by the Estate of Roger Deakin. Reprinted by permission of Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

- Excerpt from “Rilke: The Apple Orchard” in District and Circle, by Seamus Heaney. Copyright © 2006 by Seamus Heaney. Used by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Michael Hamburger, “For Ted Hughes (Oct. 29th 1998).” Excerpted, with permission, from Agenda 36, nos. 3–4 (Spring 1999): 295.