Jamie Figueroa is Boricua (Afro-Taíno) by way of Ohio and a long-time resident of northern New Mexico. She is the author of the novel Brother, Sister, Mother, Explorer. Her awards include the Truman Capote Scholarship and the Jack Kent Cooke Graduate Arts Award. Her writing has appeared in Epoch, Yellow Medicine Review, Sin Fronteras, McSweeney’s, and American Short Fiction. She is an Assistant Professor at The Institute of American Indian Arts.

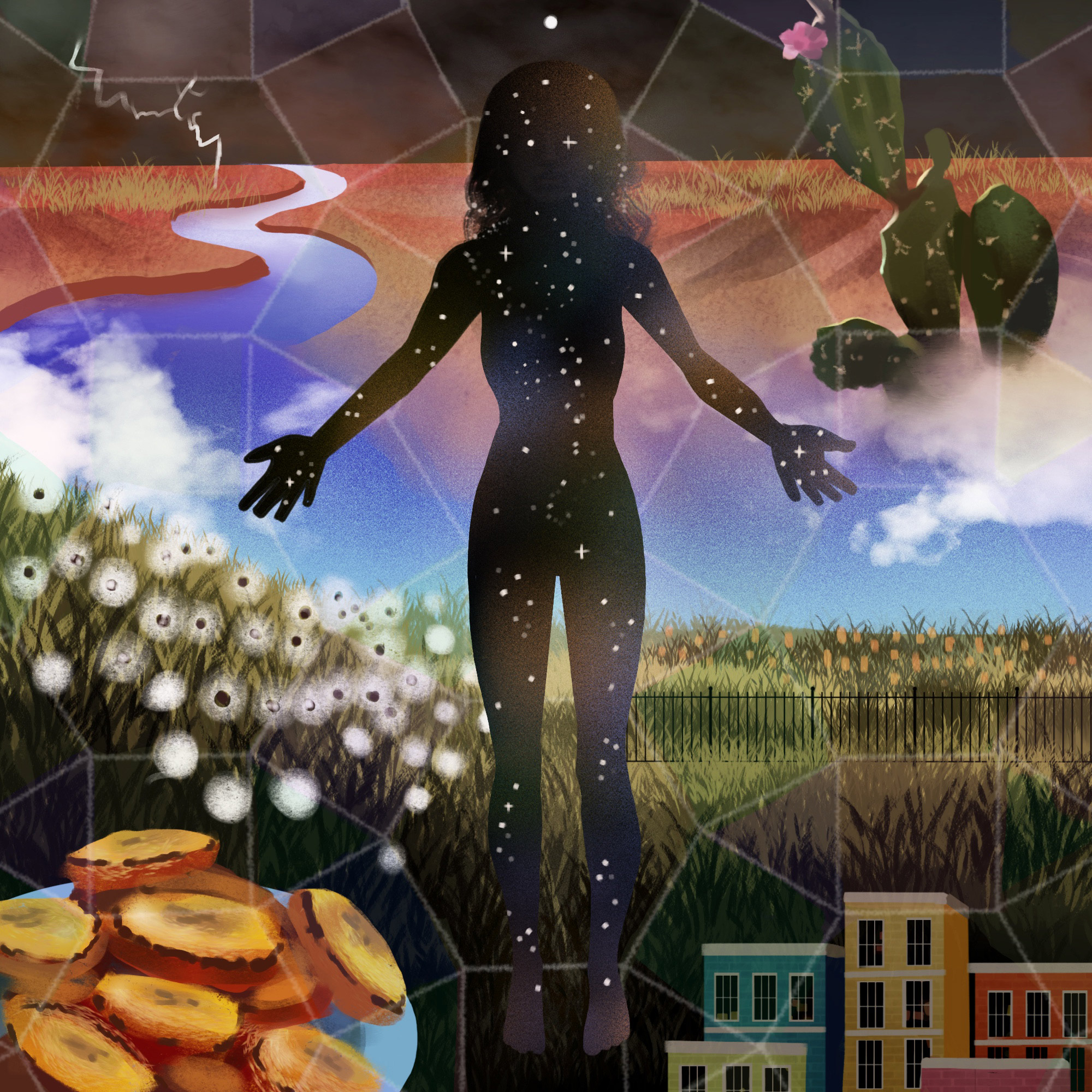

Cienna Smith is a Black and Latina illustrator and visual development artist based in New York City. Her artistic practice focuses on creating colorful work that evokes a sense of energy and life and that often delves into surrealism, her Caribbean upbringing, and painting women who look like they could be family. She is the art director for Black Womxn Exhale.

Jamie Figueroa brings her pen to the blank pages of her family’s history, navigating generational trauma and lost ancestral stories in order to reveal and reclaim her cultural and familial inheritance.

This is my “archive of silence.”1

The small lined notebook in my left hand is cumbersome. My fingers grip the sides as best they can to steady the pages. The pencil I use is dull; the soft, blunt lead digs into the space between each blue line. On this first page, I am careful to make the stems of the h’s and d’s tall. Careful to hook the g in the right direction. I can write a handful of two- and three-letter words. The spiral at the top of the notebook glints, catching the sun as the wire coil shifts in response to the pressure of my writing.

My mother and my two older sisters lie on a nubbly, yellow felt blanket in the grass. The top edge lined in unraveling satin. Kneeling behind my mother, I study her and my teenage sisters. Their arms and legs are longer than anything I have yet to experience—potential and self-possession outstretched—browning darker by the moment. Uninterrupted by trees, the backyard is vast. It rolls into one neighbor’s lawn and then another as far as can be seen. Tufts of dandelions in full bloom, and in post-blossom puff, constellate the grass. Prince plays from a small speaker lodged in one of the upstairs windows. As he cries “purple rain,” we shriek and call out with our passionate imitations. The back of the split-level seems to turn away from us, more interested in the road and who might be passing by than in our emotional outburst. Awaiting its master as if some obedient pet. At six years old, creativity moves naturally from the center of my being, down my right arm, and through my hand with each carefully crafted letter. I compose my first poem.

It is early spring. The prior autumn my mother, my sisters, and I packed the contents of our government housing in large, black trash bags and piled them into the Buick. We drove from our neighborhood of black and brown mothers, and children adorned with beaded hair, a few towns south. We were moving in with our mother’s new husband, whose home had too many empty rooms, since his own children were adults. Before this, all four of us had slept in my mother’s bed each night. That was my earliest memory of sleeping and dreaming—lodged between the bodies of a pair of older sisters, only sixteen months apart, and our mother. I didn’t have the capacity to express the longing I felt for that bed, for the exclusive unit we were, a family of the feminine. A womb of our own containment and authority, safe. To be with this man in his house, each of us in our own room, my mother the farthest away she’d ever been and out of reach in his embrace, was a betrayal of what I had come to know and trust.

As daughters, we were no longer privileged. As the youngest, I no longer had power. There was a man now, a white man, with a white beard and white T-shirts with tinted stains beneath his arms, and white cigarettes with endless plumes of white smoke snaking around him after dinner as he sat at the head of the table, his table. Endless stories from his early shift at the Goodyear plant. He rearranged our hierarchy. My mother submitted. In my limited understanding, I was confused as to how this had happened. I wanted it undone. But in the grass, on the blanket with my real family, each one of them stretched out and singing, the laughter that I knew, radiating the comfort of the familiar, compelled me to summon the sparse language that I possessed in order to capture what I belonged to and what belonged to me. A celebration.

This was before we ran, never to return. Before the next man came along—one husband after another and all the boyfriends in between—traversing our lives, rearranging us as he came and went, scrambling the cohesion of our feminine collective.

We know about trauma. We know about memory. We know about the brain. In recent years, a multitude of studies have been released detailing up-to-date science as to how each of these functions. One can read through a number of medical journals or psychology blogs and parse a basic understanding. Trauma can be defined as anything that overwhelms the nervous system. Trauma affects memory. Trauma affects cognitive function. Our ability to perceive and translate experience into story, which in turn helps us make meaning, is impaired by trauma. Trauma affects our ability to imagine. Our ability to recall the basic details of our stories can be, and often is, stolen by trauma. In its place are blanks.

If you subscribe to the information revealed by epigenetics, you have within each of your cells approximately three generations of trauma. Your body, the record keeper. An inheritance of emotional history. “Not how it was, but how it felt,” the Belarusian poet Valzhyna Mort explains in an interview about her latest book of poems, Music for the Dead and Resurrected. My memory is affected by the trauma I have experienced in my life in addition to the trauma experienced by my ancestors in their lives. My mother’s story is also my story, as are the stories of my grandparents. The handful of explicit details, often strange and incoherent—lost, found, lost—are assembled and reassembled. And, of course, there are all the blanks.

I don’t remember how many times we moved around one small, rural Ohio town before crossing the county line to another Main Street, where semitrucks had worn grooves in the asphalt, where the drive-through liquor store was not far from the collection of churches; and of course there were the fields of feed corn and soybeans, and cows in various group formations, as if painted boulders—the most uninterested of us all. I don’t remember how long the pastor and his family took us in for after we ran.

I don’t remember where I thought I was going when, at six years old, I put a pack of bubble gum, a photo of my mother, my nightgown, and two pairs of underwear into a brown paper sack and stomped out the front door. My sisters ran after me, dragging me back to the house. Laughing and crying at my ridiculous choice of belongings to pack, at my courage and desperation. At our desperation. I don’t remember the look on my mother’s face later that night when she returned from work, after hours on her feet cutting hair, and they told her. Surely it was that terrible mix of hurt and other emotions too numerous to track, let alone name. The hurt that had been unleashed on her. The hurt she unleashed on me. The hurt I learned to return.

I don’t remember how many years I used that same kind of brown paper sack as a book bag. I don’t remember how many times I was asked, “What are you?” I don’t remember how many classroom windows I stared out of as if held hostage by a roomful of people who did not look like me, aching for some semblance of the familiar, for something nourishing. The weapon of education was wielded, purposefully excluding me while demanding my subservience in return. Another kind of assault, of trauma, of being invisible, of being silenced, of being rewarded/punished for loyalty or lack thereof to the sameness I was drowning in—soundlikelookliketalklikethinklikeactlike. I don’t remember how many times I was assigned to fill out my family tree—blank after blank after blank, the defeat in my mother’s body as she looked at the stump of it, shrugging her shoulders. What kind of person can’t name those whom they descended from?

I remember the surprise of digging up potatoes for the first time, my nails thick with Ohio soil. I remember my mother starting her first barbershop. I remember roaming the woods behind our duplex—each tree extending a welcome I rarely experienced, a place to belong, where I wished on mini-toads and lay against the ground, conjuring forest spirits, contemplating clouds. I remember the first time I was surrounded by a group of neighborhood mothers and asked what my “nationality” was. Later, alone with my mother, her response—Puerto Rican. Two unfamiliar words. What exactly was an island? Where exactly did this island exist? What exactly was an ocean? The confusion of it all. Was it the year before that she showed me West Side Story on VHS tape as she slept on the couch after a long day of standing on her feet? The following week, my sister forced me to watch Scarface with her. As machine guns tore through one scene and then another, she gripped me tighter, enthralled by the violence. I kept my eyes closed, but the sound stayed in my head for days, weeks. Puerto Rican and Caribbean gangsters, criminals. I wasn’t sure what these movies had to do with us.

I don’t remember how many times I was assigned to fill out my family tree—blank after blank after blank.

My family comes from an island that is owned by the United States of America. Property, but not a state. Citizenship, but not equal inclusion. “Like a loyal battered wife who will never leave her abusive husband,” a Brazilian acquaintance once explained about island-mainland relations. There is no vote on the island that counts across the official border. You have no voice in Congress or the White House when you are located between San Juan and Ponce, between Mayagüez and Luquillo. Only when you are a (Puerto Rican) resident of Florida, Minnesota, New York, Iowa, Ohio, do you have federal voting rights. Only when you are in the arms of the mainland, within the empire’s proper grip.

The story that I assemble from scraps is that my grandfather, Aniceto, left the island in search of work sometime in the early 1940s. Before he departed, he took all of his children to live with his sister and brother-in-law in Río Piedras, where they were cared for with the help of the money he sent as often as he could. One by one, following the infection of my eldest aunt’s eye (and subsequent blindness), each of the ten children were brought to New York City. There is never any mention of his wife—my grandmother, Eda—in the migration. At some point, she is also in New York City, but blanks clutter the timing, the order; she appears and disappears. Once in the city, the eldest children were expected to fend for themselves. The youngest three were handled differently.

I kept you. At least you had a mother.

I come from the sound of mangoes thumping against the ground at night, let loose from the only branches they’ve known. I come from coquí songs. I come from the cats that pour off roofs, huddle in dry, unused fountains, and clutter in the shadows. I come from my grandfather’s dark-skinned mother, who, despite her wheelchair, held each one of her grandchildren close to her heart like the gold they were. I come from the bed where my mother and all her siblings slept, with a hole in the middle that they had to navigate for fear of falling. I come from ebony cousins who became the monsters in my mother’s warning stories of whom to fear—the darkness hidden inside you, yourself. I come from poverty, birds hunted by slingshot, winged food. I come from the stones in the river, the roots of the mangrove, the surprise of stars glittering in the water of the lagoon, the same wonders that were there generations before Columbus was born.

Assimilation feels not so much like being erased as being pasted over—thick layers of whitewashing—until a blank surface has been created on which the dominant culture asserts itself, produces a replica of itself. And while for some newcomers to this country it may seem like a choice (depending on their race and class), for many it is implicit, expected. Survival. Prohibition (from the Latin, prohibitus, “holding back”) of one’s language and free expression of culture; the force of the cross, a single understanding of God and all that goes with that; the rules of relating confined to what is allowed and regulated, and to behaviors consistent with the shoulds of the dominant culture, ruled by white-body supremacy—this is some of what must be navigated. The shame.

Trauma. Memory. The brain.

Our bodies recording.

What we need to understand and be reminded of is that trauma, memory, and the brain are not static, unchanging/unchangeable components. Rather, they are living, breathing entities, feral. They leave their trace. Trauma has its own intelligence and force; it is alive in all those who have survived it. Moreover, it’s alive in the descendants of those who were afflicted by it. First, second, and third generations have the scars, the same pattern of teeth marks and claw marks, found in the original generation who suffered the direct harm. Memory will shape-shift with age and time and perspective. Its fins become wings, wings become hide; legs, tail, and horns emerge. It seems to control you, not the other way around. And the brain? All that gray matter, some 80 percent, we can’t even access. A whole universe inside our skulls that we pretend to know, and yet, if you ask the most versed in the field, they will confess to all the dark unknown.

Your body, the record keeper. An inheritance of emotional history.

Assimilation is a kind of annihilation, even if consensual. It is this trauma and the factors which forced it to happen that dovetail with the traumas of my mother’s life (and her mother’s, father’s, grandparents’) and echo in mine. Colonization, both historical and ongoing, pulses my body. Meanwhile, I stand facing in the direction of my ancestors’ homeland, east, listening to the absence of stories.

We tell our stories and convince ourselves of who we are, where we come from, despite the layers of missing information—some of us more than others. And if you’re not able to access the resources—intact family lines, sane relatives, genealogical records, properly labeled family trees, history books where you and your kind were written into the pages—or alternatively, to speak the language your ancestors did and engage in traditional knowledge and practices, you’re left with an accumulation of blanks, superficial displays you know better than to trust. I am magnetized to what is behind and beneath. I excavate with my pen.

I don’t remember any of my mother’s weddings, all those white men. I don’t remember the temporary relatives. I don’t remember where or when they disappeared, only that they were suddenly gone, not to be mentioned again, all evidence of them erased. Even the grief missing, submerged. I remember my mother trying another church, the three of us daughters in tow. Her fitted dresses and the reveal of cleavage, her hair heated into looping waves, red lips and earrings chiming as she moved. Jesus, yet another man demanding devotion. I don’t remember how many times I tried to learn Spanish in order to speak to my mother. The words in my textbooks were not the same as the ones she knew. I don’t remember what she said to me the one time I tried to speak with her in public—only that I knew enough never to try it again. Still, whenever I invite Spanish into my mouth, my tongue thickens. My ears scramble what they hear. Is this my body remembering the nun’s punishment every time my mother spoke her language? I don’t remember how often I was left alone as a young person, both sisters having moved out as they neared eighteen. I don’t remember feeling lonely. I remember adapting to the torture of being isolated. At a certain point, I learned to take it with me everywhere I went. I don’t remember how old I was when my mother first straightened my hair, but it wasn’t as toxic as what she used on her own hair, the smell of which burned the inside of my nose.

I remember, at twelve, my limbs extending long and thin, as if plantlike, as my sisters’ had. I remember walking home with a junior high classmate whose trailer park was down the road from our apartment complex. “Watch me,” she’d said, pulling in the thin line of her bottom lip. “See if you can do yours like this.” I mimicked her, gathering all that I could into my bottom teeth. “Yes!” I had managed to reduce the size of my lips. Which meant I looked a little less like what I was, which to her was a triumph. The problem was that when I smiled, mirroring the attention and triumph back to her, I lost control of my lips and they spread, generously, revealing my large mouth and expansive smile, complete with good, strong teeth that had eaten through generations of enslavement. My inheritance—a mouth, jaw, teeth that will endure. Survive. Disappointment passed over her face. “See how long you can do it for.” As we continued our walk and she talked about what I cannot remember, I focused my attention on nodding at her and breathing through my nose, which flared my nostrils (another corrective lesson), as I held in my lips. I did not know that what I felt—the inner lining of my skin shrinking away from itself and the head-to-toe burning and tightening—was the somatic expression of shame. A feeling, embodied. Instead, I just tried to get it right. It was the performance of an identity that did not belong to me. I had watched my mother do the same. Perform a kind of whiteness. Even though she didn’t get it right, she never gave up trying to hide all that she truly was.

You already stand out. Don’t draw any more attention to yourself.

I printed maps of Puerto Rico, Ohio, and New Mexico, taped them to my bedroom wall, and, tracing each border with my fingers, tried to understand how these shapes shaped me. My triptych of un/belonging.

Soon after turning twenty, I learned how to fill notebooks, to keep my hand moving. I learned how to sit in meditation on a zafu and zabuton, following one breath and then another. I learned how to slow-walk, the steady placement of each foot, touching the trust implicit in the ground itself. I did all this beneath Taos Mountain, at the home previously owned by Mabel Dodge Luhan, with my teacher, Natalie Goldberg. Writing Down the Bones became the way I confronted the blanks, my ancestors’ and my own. With a fast-moving pen piercing the trauma, I felt it lose its grip, lessen in power. What emerged in the space it had occupied? Connection to the core of myself beneath all the whitewashed layers. Connection to what was greater than myself, to what moved in me with the sovereign knowing of my imagination.

Filling cheap spiral-bound notebooks became the way I proved to myself that I existed and that I had a right to my story, no matter how much of it had been missing and chaotic. First-thoughts scribbled into one blank and then another, page after page. I met my own mind. I felt my whole aliveness. Writing became my practice. Suspicious of most everything and everyone, I learned how to make space for what happened when my pen crossed the page. My own presence meeting the unknown, the unseen. Penetrating beyond what I presented to myself about myself, about the world, and about my place in it, to the tender, hidden underbelly—raw, kaleidoscopic, inclusive truths that I could claim. From here, I listened to what rose up to my awareness, touched my own lineage, getting at what was behind and beneath, to all those who dwelled within me, my constellation of origin. From here, story became my medicine as it narrated what I remembered and what I didn’t remember. Trusting, too, became my practice.

I come from El Yunque, pressing wet with life against my skin. Mud and waterfalls and orchids blooming in air. I come from the gods of wind, the gods of fault lines rubbing deep beneath the sea. I come from the Island of Enchantment—the state of being under a spell—a place of magic. I come from the original people—worthy, honorable people. I come from what is beneath, what has been pasted over—by assimilation, by time, by the nature of graves, by colonization—and calls out in specificity. I come from the cobblestones in Old San Juan, taken from slave ships. I come from the backs that bent as they were put into place. I come from sugarcane fields, sweetness stuck between teeth. I come from the smell of smoking meat; from chickens and horses wandering as they please; from sofrito, bacalao, plátanos, cassava, arroz amarillo; from music demanding to be heard in ears and in hips every moment of the day and night. I come from the cacophony of being alive—yelling, dancing, crying, laughing, calling out to the next generation who pass by in diapers—Mamí, Papí!

In my late twenties, during my Saturn return—when, according to astrology, full adulthood sets in—I left Ohio for New Mexico, the place I’d been regularly visiting for nearly eight years. As I shed my experience as a tourist and transformed into a resident, I considered how to introduce myself—what stories I wanted to share and how I would present them.

I printed maps of Puerto Rico, Ohio, and New Mexico, taped them to my bedroom wall, and, tracing each border with my fingers, tried to understand how these shapes shaped me. My triptych of un/belonging. Puerto Rico, the Island of Enchantment. New Mexico, the Land of Enchantment. And there in between, Ohio. If only I could get my coordinates right. I wished it were that easy, to locate the land, to locate myself. New Mexico was not Ohio, obviously and thankfully. Neck tattoos of “Brown Power” were not uncommon, most public places were bilingual, checkout ladies at the grocery store and in government offices called me “mi’ja” as only my mother, rightly so, had ever done. No one asked me what I was. Occasionally I was asked where I or my people were from. Which was not by interrogation; it was by invitation. Mountains, mesas, piñon, ponderosa pine, juniper, cedar, chamisa, cholla, prickly pear, sage. Whispers of water called river. The way that water whispers. Female rain. Coyote, bear, snake, wild cats, wild horses. Sky. All of this and more rearranged my reality. It was an external and an internal experience. Because of this, I could soften.

The white-body supremacy of the Midwest, polite racism, and the confines of small-town culture dissolved. There was more room to explore my own identity. To coax out what had been banished to the corners for fear of being unsafe. This is how it was for me, a mixed-race WOC, who always felt unsafe and tried to mimic whiteness as my mother had. I had to show my white flag of surrender to what oppressed me, as if to say, “Please, have mercy. I will not be a threat to you.”

Liberated from Ohio and my impressionable youth, I set out trying to understand and claim what colonization had stolen from me. After a fifteen-year break from academia, I finished my education at a tribal college, the Institute of American Indian Arts, during which I “returned” for the first time to my family’s homeland, Boriquén.

I listened to what rose up to my awareness, touched my own lineage, getting at what was behind and beneath, to all those who dwelled within me, my constellation of origin.

Flip-flopping through warm puddles in the streets of Río Piedras, I pass my groceries from one arm to the other, as I would a heavy baby. I’m on my way back to my desk and my notebook. As I greet the ladies in housedresses, their damp hair rolled into curlers, and pass the boy on the other side of the chain-link fence—his lips puckered into one of the wire openings, calling for my attention—something occurs to me about the triptych of maps I had taped to my bedroom wall five years prior. What I had not asked as I studied those maps was this: Do you remember me? Do you remember my family? Even those who left? Even me, the first of those born off-island? And while I could not hear the answer, I could feel it as much as I could feel the generational scars of trauma. I could feel the words of Aurora Levins Morales’s essay “Revision” in my body, in my energetic roots, claiming me:

Let’s get one thing straight. Puerto Rico was parda, negra, mulata, mestiza. . . . All of us who are written down: not white. We were everywhere. . . . When most of the indias had given birth to mixed-blood children, when all the lands had been divided, our labor shared out in encomienda, and no more caciques went out to battle them, they said the people were gone. How could we be gone? We were the brown and olive and cream-colored children of our mothers: Arawak, Maya, Lucaya, stolen women from all the shores of the sea. . . . They called us pardas libres and stopped counting us. Invisibility is not a new thing with us. But we have always been here, working, eating, sleeping, singing, suffering, giving birth, dying. We are not a metaphor. We are not ghosts. We are still here.2

I remember all the skin conditions of my teenage years. Regular trips to the dermatologist. Vigilantly watching my blood for any more antibodies that would force the doctor to diagnose me with lupus. My face losing pigment, suddenly a question mark bleached onto my right cheek—vitiligo—fought with topical steroids. Pityriasis rosea, a rash extending across my back in the shape of a great tree. The poetry of symbols. The doctor’s answer when we asked, why, how? Stress.

Trauma. Memory. The brain.

Our bodies recording.

I remember turning eighteen and going to the Marion County Courthouse with my mother and my aunt to change my surname to their maiden name: Figueroa. I don’t remember the exact date, driving there or back, or the details of the courtroom. I want to say it was a cold spring day, overcast, but I wouldn’t be surprised if I am wrong. I was raised by my mother; her sacrifices and her mistakes, her wounds and her wounding, her stories and the lack of them, were all that I knew. Years later, on the island, I heard it is not uncommon for children to take their mother’s name. Claiming the matriarchal line is our traditional way. I come from women.

I remember, ten years later in another county courthouse, Delaware, divorcing my husband: a hand-me-down version of one of my mother’s iterations, white and more than twice my age. It was a grand space, complete with carved wooden benches; tall, imposing windows; and all the formality of a 1950s courtroom movie set. The judge, robed and seated on high, asked my plans. When I told him I was headed for New Mexico, he gave his approval that I was heading home. Perhaps he assumed this because of my last name and the way I looked—my summer skin and features; long, dark, curly hair; embroidered blouse and jean skirt; dangly earrings and red lips. That Ohio was my home, had been since my first memory, did not occur to him. It belonged to, was owned and ruled by, men who looked like him and like my ex-husband, who received the property we had shared. Still, I took his misconception as a blessing and drove cross-country with all that I could load into my Subaru, looking forward to meeting the person, the writer, I had yet to become. Thankful that New Mexico would have yet another. “You can have me,” I told the land when I crossed the state line.

Shortly after turning forty, and after two decades of declaring writing as my practice, I felt an overwhelming desire to burn the notebooks I’d accumulated through diligent writing—a notebook a month. I called up comadres and rode into the backcountry of Coyote, New Mexico, to a firepit. What I didn’t understand was how hot the fire had to be, how long it would take to convert pages to ash, given that the notebooks, stacked in boxes, were as tall as I was and twice as wide—quite the entity—born of my constant effort. How long does it take for a body to be cremated? How hot the fire? Wasn’t that, in a way, what this was?

Each page was a memory detailed, proof of my existence, realizations rising up from the dark interior of my brain, from the feral breath of memory, from my body. The whole of my being. Trauma faced through the effort of somatic archaeology. Another layer, stripped. In these notebooks, blanks were filled, lifetimes cradled by my presence, a simple ceremony of pen touching paper, what could never be contained by language funneling through me. There was a fondness, myself as an old friend, a part of me always bearing witness. More of Natalie Goldberg’s teachings. This was why I had lugged them from place to place for twenty years. Thousands of pages of blanks replaced by my own hand. There was gratitude and release. As we caravanned back into Santa Fe, we smelled of smoke and purifying herbs, our tongues thick and tired as if we’d prayed for days.

I come from the stones in the river, the roots of the mangrove, the surprise of stars glittering in the water of the lagoon, the same wonders that were there generations before Columbus was born.

Three years after my first trip home to Boriquén, I returned with my mother, who had not been back since she was sent away as a girl. I watched as she struggled not to be a tourist in her homeland. On public transport into San Juan, we were just another Puerto Rican woman and her daughter. I cannot express what this meant. Only that it touched generations extending backward and forward, and that—that—was a kind of spiritual recovery.

I remember the repetition of my mother’s story. Told so many times it left me numb. Told to me when I was in my greatest pain. As if in competition for the title of best (or worst) victim. If I am to be honest, I have never let myself feel the entirety of my mother’s story, as if doing so would mean surrendering to its possession, as she has done.

She was as young as six or as old as nine and had just arrived in New York City. It was soon after she had been reunited with her older siblings and her parents. Her mother, Eda, took her shopping. There was a white dress with lace, there were black patent leather shoes, and white lace socks to match her dress. There were white gloves. There was the attention. She was clean. She smelled nice. Her hair was made to behave. Behold the sight of her. A wanted child. A loved child. Or so she must have thought, until her mother took her to the Mission of the Immaculate Virgin on Staten Island. In my mother’s story, she is left on the front steps of the orphanage.

Her mother left her. There.

Where my mother cried all day and all evening until they took her in. She grew up in that institution, leaving only when she could make it on her own at barely eighteen. In exchange for food, clothing, a bed, and an education, she was given the Catholic variety of God, along with English, and was accounted for. I have never seen a photograph of my mother as a child. The youngest I’ve seen her is around nineteen in an army photograph as she was leaving one institution and was headed to another that would behave in much the same way, providing some things while violently stealing others.

This is her story: She was given away. She was left. She was not wanted. Her trauma, this trauma, formed a wound. There have been times in my life when I knew this wound better than I knew her, better than I knew myself.

Don’t trust those who are related to you. Don’t trust those who look like you.

Our week together in Boriquén had almost ended when my mother insisted that we pay an unexpected visit to her family’s homesite and the legendary, feared cousins. After circling a neighborhood with unmarked houses for nearly two hours, we found ourselves standing in the middle of the street in front of a house that, like many of the houses, was in a state of disrepair. It was surrounded by a high fence, and the gate had been wrapped in chains and padlocked. There was no way to knock on a door. We couldn’t get that close.

My mother cupped her hands around her mouth and began to call the names of her cousins in a voice I imagine was the voice she used as a child, before she left, before she was left, before, before, before. A man appeared, darker than my mother, with features similar to hers. As he unwound the chains and unlocked the gate, he smiled the same smile I see when I look at my mother, when I look at myself. Those teeth. That mouth. My inheritance.

My mother knelt at her uncle’s feet, our oldest living relative, for nearly an hour, flooded with a telling I could not understand because of my poor Spanish. I tried to read her eyes, but they were too chaotic. He—along with his wife, my grandfather’s sister—had cared for my mother and all her siblings as New York was catching and reeling in her parents.

Later, when my mother’s eyes seemed to focus again, I asked her what her uncle had said to her. After a long pause, she said it was hard to understand him.

That she didn’t remember.

Because I could see her distress, and sense how tender she was, I did not ask again.

I come from fragmented stories, trauma-splintered stories that are not mine to repeat—too much, too much, too much. I come from children who were abandoned, who grew to be women. I come from women who were held down. Women who left their children and took in others. I come from women who fought back, who wielded knives, who shot guns. Wounded, wounding. Healed, healing. I come from Taíno women and Yoruba women. Black-skinned and brown-skinned women. I come from women who can lie so good, they can convince even themselves. Women who were remade, unrecognizable. Women who have started over too many times to count. I come from women who were deterred from their own wild knowing. Women who survived.

I come from.

I am from.

I am here.

I.

Am.

The woman who—by her own hand, through her ancestors’ hands—is writing into her remembering.

- From an interview with Valzhyna Mort: “Their deaths fell into a kind of archive of silence.” Valzhyna Mort, interview by Noel King, Morning Edition, NPR, November 9, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/11/09/932977458/belarusian-poets-latest-work-is-a-legacy-of-violent-deaths-in-a-family.

- Aurora Levins Morales, “Revision,” in Remedios: Stories of Earth and Iron from the History of Puertorriqueñas, (Boston: South End Press, 2001), xxxii–xxxiii.